How it Feels to Die: An ayahuasca journey

Ayahuasca is a sacred hallucinogenic plant that has been used by Amazon tribes for centuries. In 2016, I travelled to the jungle in Peru to take part in this ancient ceremony. This is my story.

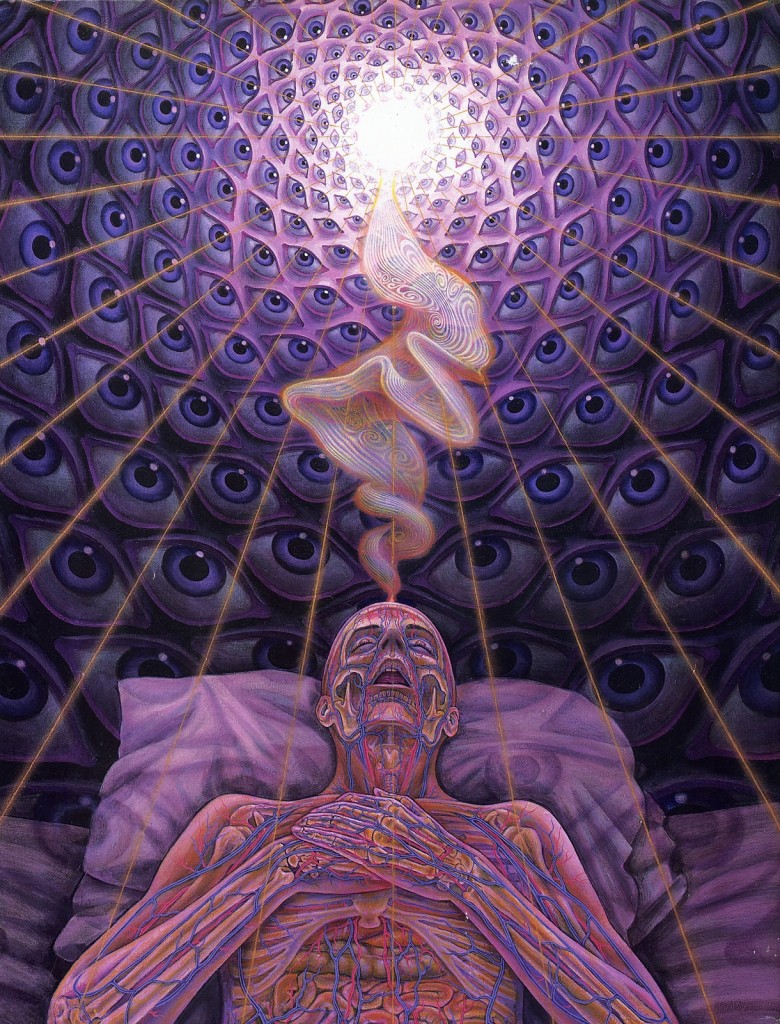

As I sink through the floor into darkness, I lose myself. I am weightless in space with my arms crossed over my chest. The cold enfolds me and leaches into my core. My skin tightens around my aching bones as I descend deeper into wide, open nothingness. There is a rectangle of light above me in which faces begin to appear. They are my family and friends looking down on me and I feel profound love for them. I’m gripped by loneliness, but not only in the sense of being alone. It’s as though every meaningful connection I’ve made with another person has suddenly been lost. It feels like my body is expiring. But I still have my mind and with it, I think: This is how it feels to die.

For an unknown amount of time, while sprawled on a thin, foam mattress in a wooden hut in the Amazon Jungle, death was my reality.

The vision came to me during my second ayahuasca ceremony at a plant medicine retreat called El Jardin de La Paz – The Garden of Peace – near the city of Tarapoto in northern Peru.

Ayahuasca (eye-ew-ask-ah) is a powerful hallucinogenic brew and one of many sacred plant medicines. It has been used for centuries by the jungle tribes of South America for healing and enlightenment.

In 2008, the Peruvian government recognised ayahuasca, made from the ayahuasca vine and chacruna leaves, as “one of the basic pillars of the identity of the Amazon peoples”. It claimed ayahuasca consumption “constitutes the gateway to the spiritual world and its secrets”.

Ayahuasca is becoming increasingly popular with Western tourists seeking healing, spiritual awakening and guidance. For the less reverent, it’s a new way to get high.

Ayahuasca is becoming increasingly popular with Western tourists seeking healing, spiritual awakening and guidance. For the less reverent, it’s a new way to get high.

Every year, thousands visit Peru’s so-called healing centres and retreats for ayahuasca ceremonies, drawn by claims that one ayahuasca ceremony is equivalent to years of therapy.

Although it’s illegal in America, ayahuasca has been growing in popularity in Silicon Valley, New York and Los Angeles, with a generation that’s embraced wellness trends such as meditation, ‘clean eating’, CrossFit and yoga. A recent New Yorker story suggested that, in the same way that cocaine was the jittery, keyed-up drug of choice for upwardly mobile types in the 80s, ayahuasca is the punishingly self-improving drug for today’s ‘Age of Kale’. It’s now vogue enough that talk show host Chelsea Handler tried it in her latest Netflix series.

I had been interested in ayahuasca and its psychedelic ingredient dimethyltryptamine (DMT) for many years.

DMT occurs naturally in dozens of plants and has also been found in mammals, including humans. Untested hypotheses suggest that DMT is produced in the human pineal gland and may be involved in eliciting dreams and the near-death experience phenomenon, where people report seeing life flash before their eyes.

Travelling across South America in 2016, ayahuasca was in the back of my mind, but I never thought I would end up drinking it.

It was a conversation over breakfast at a hostel in Puno, Peru, with a guy who had just returned from a 10-day ayahuasca retreat, that set me on a path for the jungle.

Get life-altering ideas like these in your inbox.

Sign up for the newsletter here.

I didn’t really know what we were getting into.

I exchanged a few emails with Lara, the co-owner of the retreat. There was a medical declaration to fill out with questions about previous drug use (not much) and mental health conditions (none that we knew of).

We had deposited money into Lara’s bank account and had instructions to meet at a cafe in Tarapoto at 9.30am on a Monday.

There were other instructions, too: No fried foods. No refined sugar. No caffeine. No dairy products. No pork. No drugs or alcohol. No sex. None of this for at least 48 hours prior to the retreat.

“Basically, fresh clean and natural foods with a high ratio of fresh vegetables and fruit is the best way to prepare,” El Jardin’s website says.

To prepare myself mentally, I watched documentaries and Youtube videos about ayahuasca. I had read articles about ayahuasca apparently curing people of depression, anxiety and other illnesses, as well as accounts of profound hallucinations, revelations and spiritual encounters.

But I had also read stories of death, murder, bad trips, phoney shamans, burglaries, and rape on retreats.

–

I’m the first to arrive at the cafe in Tarapoto, a humid, commercial hub in the Peruvian Amazon, where it seems there are more motorbikes than people.

I’m worried that the five others joining us on the retreat are new age types, obsessed with yoga, meditation and vibrations.

I’m not a spiritual person, I’m too inflexible for yoga, and I’ve only used guided meditation videos on Youtube to help me sleep

Lara’s the first to arrive. Born and raised in New Zealand, she runs El Jardin with her partner, Ashley, from England, who bought land in the jungle and built the retreat in 2014.

I’m introduced to Sam*, a naturopathy graduate, former musician and drug addict from Sydney, Australia. Sam’s friend Charlotte, who recently lost her father and separated from her husband. Mitch, a 20-year-old college student from the United States who believes he’s destined for greatness. Jack, a 60-year-old from the US who has lived the “high life” but is searching for “something more”. And Christian, a seven-foot giant, also from the US, who’s been to Kenya a couple of times and talks about it a lot.

Everyone’s here for a reason, though I’m not yet sure of mine. I tell the group I’m “at a crossroads” and “seeking direction in life and a deeper connection with nature”. I’m almost 30 and, like most people, I don’t know what my “purpose” is. I guess I’m here because I’m desperate to know.

Do I really believe that tripping on ayahuasca might provide the answer? That a plant might reveal to me the meaning of life? I’m sceptical, sure. But I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t think it was possible.

The nine of us load our bags onto a five-seater jeep and ride for about 90 minutes through a town and a village, over mud tracks (we got stuck – twice) to the retreat, hidden down a long driveway in the dense, green jungle.

“This is not a holiday in the jungle,” Lara says on arrival.

“A lot of people make the mistake of thinking it is. It’s not. It’s hard – really hard. But if you can stick it out, it’s worth it.”

–

Arturo, a Peruvian volunteer and plant medicine student, escorts us to our open-air, wooden huts.

Silence and solitude are as important to the experience as the medicine, we’re told.

Touching one another and socialising is also discouraged as it’s said to disrupt people’s “energy”.

My hut’s small and smells damp. It has a single bed with a white mosquito net, a shelf made from a crate which holds an eight litre bucket of spring water and a candle. There’s a small balcony with a hammock and a broom in the corner by the door.

I lay out my things – a journal, torch, rain jacket and jandals – sit on the edge of the bed, and listen to the river below and the ensemble of birds and insects outside.

In the afternoon, we all meet in the hut, known as a maloka, which is circular with a thatched, cone-shaped roof. It is said to be a sacred and protected place.

There are candles, crystals, a statue of the Buddha and pounamu from New Zealand laid out like an altar in the middle. Our mattresses are spread evenly around the edge of the room.

We’re introduced to Hegner, the resident shaman or curandero (healer) at El Jardin, who leads us in the first plant ceremony of the retreat – a tobacco cleanse.

Tobacco is considered a “master plant” in Peruvian culture, which is said to purify and act as a communicator between man and the spirits.

The point of a tobacco cleanse is to vomit – a lot – so that your body is more receptive to the ayahuasca.

Hegner, who devoted 11 years to studying and dieting the “master” plants of the jungle as an apprentice shaman, pours each of us a cup of tobacco tea, which tastes like a cigarette smoothie and burns my throat.

Each of us then has to drink four litres of water as quickly as possible.

Each of us then has to drink four litres of water as quickly as possible.

It doesn’t take long for me to start vomiting violently into my yellow plastic bucket.

Just the thought of drinking any more water makes me feel sick, but Arturo continues to fill up my plastic jug.

I drink and vomit for about 20 minutes until I have consumed four litres of water.

I feel hazy, weak, and vaguely euphoric. Barring a few regrettable nights of excess hard liquor, I have never endured such self-inflicted suffering.

Ashley tells us to empty our buckets in the river and return to our huts for the night.

–

Arturo delivers dinner just before dark.

It’s soup made with quinoa, cabbage, carrots, potato, lentils and lemongrass. El Jardin serves only bland, clean meals made using fresh ingredients that apparently won’t interfere, or react badly, with the plant medicines, particularly ayahuasca.

This is necessary because many foods, especially those that are aged, preserved or overripe, contain high levels of a compound called tyramine which, when combined with a chemical found in the ayahuasca vine, can have side effects, including severe headaches and, in extreme cases, cardiac arrest.

We only get one or two meals a day, so I sip my soup slowly, taking care to taste the individual flavours.

Alone in the jungle at night, without the stimulation of technology and activity, my thoughts unravel.

They are loud and scrambled, impossible to decipher from the chorus of crickets and what sounds like a brass band in the distance.

–

In the morning, Arturo and Hegner stop by to give me the second “master” plant – mucura – a spicy white root that is said to energise, fortify, detoxify and protect body and spirit.

It’s served as a warm broth in a glass and tastes like concentrated foliage. I fight the urge to throw it up.

A half hour later, Arturo arrives with breakfast – broccoli, cabbage, cucumber, carrot and stodgy rice with a banana.

After eating, I go down to the river to wash.

I spend the rest of the day in my hut, on the hammock and in bed, worrying about ayahuasca.

I spend the rest of the day in my hut, on the hammock and in bed, worrying about ayahuasca.

Ashley had advised us to set intentions for our ayahuasca ceremonies, to meditate on what we want to get out of the experience.

Unlike many tourists who come to the jungle for healing, I don’t feel like I need it. I consider myself a happy, balanced person with no known health conditions or emotional baggage. Life is just fine without ayahuasca.

But it’s been said that you don’t choose ayahuasca. Ayahuasca chooses you.

–

Soon after sundown, when the jungle is cast in a grey-blue light, I leave my hut and walk the garden path to the maloka.

I remove my shoes at the entrance, carefully place my torch, drink bottle and backpack by my mattress and sit cross-legged, believing that it makes me look spiritual.

My stomach is empty and twisted and I can feel a pulse in my neck.

Ashley, wearing indigenous ceremonial clothing, lights two candles and a bowl of palo santo, a scented wood, in the middle of the maloka.

He blows smoke from the burning wood over each of us, which is said to ground “energies” and keep mosquitos away.

One by one, we rise from our mattresses and walk over to Hegner, who is wearing his long, dark hair down past his shoulders, to receive our cup of ayahuasca.

He pours the brew – a thick, brown sludge – from a glass bottle into a small wooden cup and blows tobacco smoke over my head and into the cup before handing it to me.

I take a deep breath and pour it into my mouth, tipping my head back to get every last drop. It’s gritty and sweet, like pureed dates and dry leaves.

I walk back to my mattress and sit with my back against the bamboo wall.

Everyone is quiet. It’s supposed to take up to an hour to feel the effects.

Everyone is quiet. It’s supposed to take up to an hour to feel the effects.

It is gentle at first. I see colourful lines moving, like sound waves, through the darkness.

My head starts to feel heavy and fuzzy so I lay on my back.

I close my eyes and see visions of colours and chaos. They are senseless and wonderful.

I attempt to rationalise what is happening to me. This is just serotonin and dopamine flooding my brain, I tell myself. This is all in my head.

I resist going where the ayahuasca is taking me.

But the moment I hear the faint rustling of Hegner’s chakapa – a rattle made of bundled leaves – my mind leaves my body.

I am filled with indescribable joy, love and warmth. I gasp for air and smile uncontrollably. Tears well up in my eyes.

I fall in and out of abstract visions. All of my senses are heightened. Hegner’s icaros (ceremonial songs) are the most beautiful sounds I have ever heard.

His chants follow repetitive rhythms, but the melodies and volume fluctuate. Changes in his voice seem to alter the temperature in the maloka, as well as the direction and intensity of my hallucinations.

I can hear others spewing into their buckets. It’s common for people to purge – vomit, go to the toilet, cry – on ayahuasca.

Hegner calls each of us to receive a personal icaro. I sit in front of him while he chants and taps the chakapa on my head.

He hands me a tobacco cigarette, which is said to contain the prayers he has sung over me, and I return, unsteadily, to my mattress.

Six hours have passed when Hegner circles the room to light our cigarettes, formalising the end of the ceremony.

![]() –

–

Breakfast is peas, spinach and yuca. Although I haven’t eaten for 24 hours, I can’t finish it.

Arturo has arranged for me to take a flower bath, a ritual that typically follows an ayahuasca ceremony.

The bath is a bucket filled with flowers, leaves, scented oils and water. I’m told to stand facing the sun focussing on my intentions for the retreat: Clarity. Purpose. Nature. Healing.

Taking a scoop of water from the bucket, I pour it over my head. It smells like perfume and lemongrass. I turn full circle to my left, then my right, pouring a jug of water over me each time.

Arturo says flower baths are used to wash away negative energies and to protect us from unhelpful spirits. All I know for sure is that it’s more refreshing than a hot shower.

–

After three days, I am adjusting to solitude, silence and hunger, passing the time by exploring my thoughts and reading a book, prescribed by Lara, loosely about understanding women and being a man.

On day four, I revisit my intentions for the second ayahuasca ceremony.

Tonight, I want to be taken deeper, I write.

I want healing. I don’t know what for, but I trust that the plants and my mind do. I have to have faith tonight. I have to let go.

–

–

With my back against the wall of the maloka, I sit and wait for the ayahuasca to take hold.

This time I will surrender, I tell myself.

I hear Hegner shaking his chakapa and chanting softly, but the music doesn’t transport me this time. So I wait.

Then, like the seamless transition from waking to sleep, I sink through the floor into what feels like another realm.

Between fantastic visions, colours, patterns and movements, I experience moments of clarity where I sense that I’m being shown something meaningful, such as being cradled by crawling vines and feeling the motherly love of nature.

This journey of the mind is not linear. Each vision is fleeting. They fragment like Picasso paintings, making way for new and – in this case – progressively darker encounters.

Until, suddenly, I realise I am dying.

I’m descending into a dark grave. My flesh is decaying, revealing my bones. I feel completely hopeless, cold and detached, but I’m at peace. I understand that death is inevitable and confronting it allows me to live without fear.

I wake from the vision and attempt to ground myself in reality, but I’m swept away again.

My mind is spilling out the back of my skull in a torrent of brilliant light. It’s like everything I’ve known – beliefs, stereotypes, prejudices – is being emptied from my brain. A factory reset of my consciousness. I’m groaning and writhing on the mattress. It hurts to let go of ideas, but I feel no tangible pain. Every muscle in my body is tense. With my neck arched back, I open my mouth wide and gasp.

It’s like this is my first breath.

–

As I come to senses on the floor of the maloka, I search for meaning in what I have just experienced. I have seen and felt things that I struggle to explain rationally.

I came to El Jardin seeking direction and purpose. Instead, I saw my death and the emptying of my mind. I’m no clearer as to what to do with my life. All of the travel, hunger, solitude, meditation and vomit, for this? I have no answers.

But there is more. I came to El Jardin a sceptic, but my concept of reality is no longer limited to what my five senses can perceive. I know the mind is powerful, but surely this was more than just an ayahuasca-induced dream. It was as real to me as anything else. Not spiritual, or transformative – but real.

Holding an unlit tobacco cigarette in my palm, I curl up on my mattress and let Hegner’s icaros wash over me.

* All names of participants in the retreat have been changed.

Get life-altering ideas like these in your inbox.

Sign up for the newsletter here.

This article was originally published in 1972 Magazine.